Creatine is one of the most well-studied and effective supplements for strength, performance, and muscle recovery — but not all delivery formats are created equal. As creatine gummies rise in popularity, so does the number of ineffective or misleading products on the market. AKA, 'Fake Creatine Gummies'.

Here’s how to evaluate whether your creatine gummy actually delivers what it promises — backed by science and basic formulation logic.

🧪 1. Creatine Monohydrate Can’t Be Clear

Logic:

Creatine monohydrate is a white, crystalline, poorly soluble powder. When mixed into a gummy matrix, it cannot dissolve fully or become transparent — especially without chemical modification or extreme processing.

If a gummy is completely see-through, it likely contains:

-

Too little creatine to be visible

- A form of creatine other than monohydrate (often unlisted)

-

Or no creatine at all — just sugar, gelatin, and flavoring

Scientific Support:

Creatine monohydrate’s solubility is limited to ~14 mg/mL at room temperature [1]. It does not fully dissolve into most solid or semi-solid matrices (like gummies) without leaving visible particles or cloudiness.

💧 2. Moisture = Creatine Breakdown

Logic:

When creatine is exposed to water — especially in acidic or warm environments — it degrades into creatinine, a biologically inactive compound. This is a critical issue in soft, gel-like gummies that retain high moisture content.

Why it matters: If your gummy feels soft, wet, or jelly-like, it may already be degraded before you take it.

Scientific Support:

Studies have shown that creatine monohydrate rapidly converts to creatinine in aqueous solutions, particularly at low pH or elevated temperatures [2].

“The degradation of creatine in solution is primarily a function of pH and temperature, with the formation of creatinine as the main byproduct.”

— Jäger et al., Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition (2011) [3]

👅 3. Taste and Texture Should Reflect Real Formulation

Logic:

Real creatine has a slightly bitter or sour flavor and gritty texture. A properly formulated gummy will either:

-

Retain a slight graininess or aftertaste

-

Or use sourness (citric acid) to mask and stabilize the creatine

If your gummy is silky smooth, overly sweet, and tastes exactly like a candy bear — it likely isn’t delivering real creatine.

Why some graininess is OK:

It’s a sign that creatine hasn’t been overprocessed or dissolved away — which supports stability and dosing accuracy.

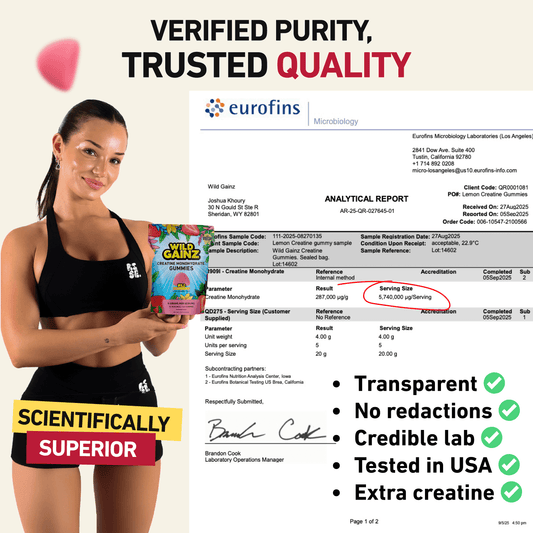

Brands like Wild Gainz have mastered the right balance between smooth texture and effective dosing, delivering great taste without compromising performance.

⚖️ 4. Small Gummies with Big Claims Don’t Add Up

Logic:

To effectively hold 1 gram of creatine monohydrate, a gummy must weigh around 3–4 grams. This is due to the physical bulk of creatine and the need for stabilizers, flavoring, and structural components.

If a gummy weighs less than 3 grams and claims 1 gram of creatine, it’s either:

- Severely underdosed

-

Or using misleading labeling (e.g., per serving, not per gummy)

Scientific Support:

This dosage-to-mass ratio is standard in supplement formulation due to creatine’s density and required binding agents [4].

✅ Summary: Spotting a Fake vs. Real Creatine Gummy

Indicator |

Fake or Poorly Made |

Real or Well-Formulated |

|

Appearance |

Clear, glossy, jelly-like |

Opaque, dense |

|

Taste |

Tastes like candy, too sweet |

Slightly sour or neutral |

|

Texture |

Silky smooth |

Slight graininess possible |

|

Gummy Size |

Small (under 3g) with big claims |

3–5g per gummy for 1g creatine |

|

Testing & Origin |

No info or vague claims |

3rd-party tested, USA/EU made |

Final Word

Creatine is a science-backed supplement — but only when it’s delivered properly. Transparent, candy-like gummies may look appealing, but they likely don’t deliver the performance benefits you’re paying for.

Look past the marketing. Use logic. Trust the science.

References

-

Wyss, M., & Kaddurah-Daouk, R. (2000). Creatine and creatinine metabolism. Physiol Rev, 80(3), 1107-1213.

-

Hultman, E., Söderlund, K., Timmons, J. A., Cederblad, G., & Greenhaff, P. L. (1996). Muscle creatine loading in men. Journal of Applied Physiology, 81(1), 232-237.

-

Jäger, R., Purpura, M., Shao, A., Inoue, T., & Kreider, R. B. (2011). Analysis of the efficacy, safety, and regulatory status of creatine monohydrate as a dietary supplement for muscle performance. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 4(1), 6.

-

Buford, T. W., et al. (2007). International Society of Sports Nutrition position stand: creatine supplementation and exercise. JISSN, 4(1):6.